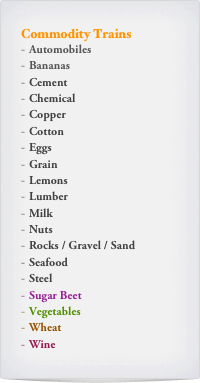

Southern Pacific Lines

Coast Line Division

“The Route of the Octopus”

Southern Pacific Lines

Coast Line Division

“The Route of the Octopus”

Automobiles (by Tony Thompson)

Auto Assembly Plants (1953)

Both Ford and GM had assembly plants in California. Auto assembly plants in both the Los Angeles area and in the Bay Area received most parts deliveries directly from plants predominantly in the east, but partial loads of parts were sent between plants via the Coast Line. Here are some of the plants:

Los Angeles:

(GM/Chevrolet) in Van Nuys (called “Gemco” by SP) (Chevrolet) plant at Raymer and also a BOP (Buick-Olds-Pontiac) plant in South Gate; (Ford) and Studebaker plants in Long Beach; (AMC/Nash) in El Segundo; and (Chrysler) east of Vernon.

Bay Area:

(GM/Chevrolet) in Melrose (Oakland) and Warm Springs; Ford in Richmond. GM had a plant in Fremont as well.

Automobiles which were assembled at those plants were then shipped around the west, along with assembled cars coming from the east (mostly models of automobiles not assembled on the west coast). Hadley took all of the assembled Ford products generally to the 11 Western states.

Auto Traffic

Thus there are two kinds of traffic: auto parts, much of it in specially equipped box cars; and finished automobiles, usually in double-door 50-foot cars. The loaded traffic, of course, is complemented and almost entirely balanced by empty equipment of the same type, moving in the opposite direction to return for reloading.

Specially-equipped cars, usually with loading racks, were extensively used for this traffic. The presence in a car of loading racks, which may or may not make the car unsuitable for general merchandise traffic, is indicated by a white stripe on the door (on the right door of a double-door car), at about 1/3 of the door height. Cars, which contain racks, so designed that they are stowable, permitting use of the car for merchandise loading, carry AAR class designation beginning with “XM”, as in XMR.

The car’s AAR class may also reflect fixed equipment, with such designations as XAP for auto parts. Most parts racks were not stowable. The 50-foot single-door cars were often in auto parts service. Typically the “stripe” (auto rack) cars, and any other cars in assigned service, are returned empty to origination point for reloading. Others are subject to confiscation for merchandise loading. Note that some regular XM cars are also used for parts loading.

Shipping of automobiles in 1952

The other side of the auto traffic is assembled or set-up cars. Most assembled automobiles delivered to the West Coast originated in Detroit and moved via Chicago onto the Overland route, or were shipped from St. Louis or Kansas City, and moved, respectively, over the Cotton Belt and Golden State routes, giving Coast Line loads in both directions. Cars assembled in LA or the Bay Area may also move in either direction for eventual delivery in various parts of the west. This includes Ford automobiles assembled at Long Beach, served by ATSF, which were shipped in ATSF auto cars for Coast Line destinations.

In 1952, railroads were shipping around 40% of the new autos though it would fall nearly to 10 pct by the end of the decade. The auto rack would bring the proportion back to about half in the 1960s. Practically all rail shipments were necessarily in auto boxes (defined then as double-door cars). There were earlier pioneer auto racks, but no significant rail shipments by that method until about 1959.

Tony Thompson.

Auto Docks

Many automobile dealers received car shipments at a Public Auto Dock. A list of Pacific Electric customers for 1952 showed 37 public auto docks where automobiles could be shipped to. The number of car dealers that used these auto dock at some stations were greater than all the other customers at that station. Fullerton listed 14 customers serve there and 12 were auto dealers. This was an extreme, but there were a significant number at most stations with auto docks.

An example in 1948: a Studebaker dealer in West Los Angeles would get notice that the cars would be ready to unload from a boxcar at a dock near the corner of Santa Monica Blvd. and Sepulveda. This was on the Pacific Electric line. They would be usually brought in at night. There were four of the Studebakers in the boxcar. They would unload the lower cars first by rotating the wheel racks then driving them out the door. Then they would handcrank the racks to the lower position and get the other two cars out of the boxcar.

Modeling Auto Trains

Use mostly 50-foot long cars, to reflect post-World War II practice, and (by AAR definition) double-door. A few 40-foot double-door cars and 50-foot single-door cars should be included, all of which can be mixed in cuts of auto cars. Rather less than half should be designated auto parts, just because the bulk of AP traffic arrives directly in LA or the Bay Area. Many parts cars are lettered for appropriate originating roads (C&O, GTW, DT&I, NYC, PM, PRR, WAB) or from pool roads (ATSF, MP, NKP, RI, SSW, SP and UP) for eastern traffic, as well as SP and ATSF cars for western traffic.

In addition, some regular XM cars are in parts service, while some “auto cars” (meaning double doors, in AAR parlance) are classified XM or XMR and can be used for merchandise. Cars designated XAP or XAR cannot be used for other than auto parts or automobile shipping assignment. Cars classed XML are largely PD cars or equivalent, and would probably be restricted to auto parts.

Reference

America’s Driving Force: Modeling Railroads and the Automotive Industry, Walthers, Milwaukee, 1998. The book is out of print, but can usually be found at used book dealers on the Internet. It does not contain great detail about the 1950s, however.

Bananas

Banana trade was big business on the west coast with the importer “United Fruit Company”.

Importing

Huge bunches would be harvested in the tropics and hung on racks in ships. Bananas were transferred from ships to refrigerator cars, in New Orleans dated 1930. Images are posted in the Photos section. The banana boats docked in China Basin (where the stadium is now). Bananas were uploaded in bunches from the ship for Castle & Cook, on a conveyor belt near Espee's Third & Townsend depot in San Francisco.

On the Coast Division in the early 50s, all on the SF extra board looked forward to banana boat days, usually on Fridays. Typically, two extra switch jobs were called not at Mission Bay but just north of it, on the China Basin channel behind what is now the SF Giants ball park, usually operating with 1200s at that time. For some reason these extra jobs usually got an early "quit", thus working six or less hours of an eight-hour shift and were popular assignments. The San Francisco banana terminal is shown by two photos in the PFE book, page 372. For a map showing the location, see Signor's and my "Coast Line Pictorial" book, page 2.

Tony Thompson

“United Fruit Company”. had docks at Wilmington (Los Angeles), San Francisco (a block from Third and Townsend) and Seattle.

Bruce Conklin

There was also banana dock at Port Huememe on the Ventura Cnty Rwy. Connecting with SP at Oxnard.

Jon C.

Produce House

In a produce house they unloaded bananas. They were stacked on the floor, the tree end of the stalk down, that made the hands of bananas point down. They would pick them up and turn them top to bottom and hung them on a hook of a conveyor that was extended from the warehouse into the car. When all the hooks were full, they pushed them in to the warehouse and into the room they wanted them in. They had three rooms, one was at 50 degrees holding the green bananas. The second room had the temperature turned up to 70 degrees so the green bananas would ripen. The third room was the working room where they were cut and put in to baskets for delivery to the stores. When the working room was empty it was set to 50 degrees and it became the holding room and they would put the next cat in there. The ripening room became the work room and the first holding room would become the repining room. Around and around it went. They received 3 cars a week and once in a while would get a forth.

Shipping in the ‘50s

The method used into the 1950s was transport by bunch. At that time, all of the labor in cutting the bunches into hands (what you see in the stores today) was applied at the produce wholesaler level. The bananas were handled in bunches, by conveyor, and weighed on platform scales before loading into the reefers. Obviously very labor intensive. The "banana box" is about 36"L x 16"W x 14"H, and reads "A. Levy & J. Zentner Co., Sacramento, Calif. Banana Box. Return to Warehouse Promptly". Has an image of a bunch of bananas on the side. In 1949/50, the boxes were a metal frame and canvas sides like the post office use to day. They were returned for reuse.

The reefer cars had similar racks for transporting the fruit from the ships to the inland wholesalers and grocery chains large enough to consume whole railcars full of bananas. This shipping produced a lot of bruised unripened fruit. It also allowed tropical bugs and snakes to gain entrance to this country.

Banana Trains

Banana trains worked out of Dunsmuir in the 1950s and early 1960s. Each banana train was accompanied by a “Banana Messenger” who cared for the welfare of the bananas. This man rode in the caboose with the train crew and whenever the train stopped he would walk up and open the doors on some of the cars to check on the bananas. He was monitoring the temperature in the cars. The train crews made this man welcome on the caboose, knowing that at some point in the trip he would bring back to the caboose a large stalk of bananas to share with the crew. There were always enough that each crewman could take a large hand home with him. The regular banana train ran every Friday and consisted of a number of banana cars tacked onto the rear of a regular freight train such as the NCP. When the longshoremen were out on strike, as they often were in those days, we would see solid trains of perhaps 80 or 90 carloads of bananas.

In San Francisco, most of the banana trains departed Mission Bay Yard in the late afternoon or early evening and ran as a TBX (trans-bay extra) to West Oakland for movement east. Sometimes,they ran as a section of #444 (to West Oakland) or #402 (from Bayshore to Tracy).

Modern Times

The advent of mechanical refrigeration revolutionized banana shipment. The bunches were cut into hands in the tropics, where the labor is cheaper, branded with labels, and packed in 40 pound boxes. The boxes were shipped to major ports and distributed, now mostly by truck. The container age has seen the boxed unripened fruit packed in refrigerated containers. Nowadays the green bananas are ripened with gas at the grocery chain's warehouses.

In Los Angeles Harbor, at the bottom of "A" Yard, United Fruit had a banana wharf for unloading ships into reefers which the were iced (despite what Chiquita says) with huge slabs of ice. These were iced via a chute and also blower ice for perishables that needed it directly applied. Now bananas are shipped already loaded into containers. These come in via refrigerated containers which also handle other items that had to be unloaded in bulk and now utilize unit double stacks.

References

A great web site on the history of unloading bananas by the United Fruit Company at the Port of Los Angeles onto the Southern Pacific. There is some interesting animation, including movies showing the unloading and transfer to rail cars, and a simulation of a ship arriving, transferring the load, and the trains and trucks departing. It's at:

There are several references to unloading bananas at Mission Bay, including one by the University of California San Francisco:

that includes this statement:

"Mission Bay has served as an important freight warehouse area for Southern Pacific Railroad, a loading zone for the United Fruit

Company's banana boats, and more recently, as the site of a houseboat and boat community."

The Illinois Central Society had a superb issue of their magazine a few years ago, devoted entirely to the banana traffic. There are many different varieties of bananas. "Burro, Red Bananas, Yellow, and Plantains.

Modeling Bananas

Unloading bananas at a local freight shed makes a nice scene to show the labor-intensive nature of freight handling during that era.

Cement

Moving Cement during the steam era

Bagged Cement

The use of bagged cement continued, particularly for individual use, for some time. The shipment of bulk cement naturally changed rather quickly to covered hoppers (there is evidence that SP did not acquire them as fast as shippers would have liked).

In the late '20s or early '30s, a photo shows large bags of cement were unloaded from a flatcar. The use of bagged cement continued, particularly for individual use, for some time. SP did this kind of loading from the late 1930s into the World War II era. It was not very satisfactory for shippers, consignees, or the railroad, and was discontinued as soon as possible. An interesting 1940 photo at the Monolith plant, shows, of course, all box cars at that time. It is in SP Freight Cars, Vol 4.

In the January 1992 issue of Model Railroader (pg. 159), a reader described a conversation he had with a Mr. Jerome Warner, a long-time worker and official at the Monolith cement plant, about how cement was shipped prior to covered hoppers:

"First, cement was blown loose into specifically lined boxcars. Second, it was loaded into boxcars in 100 lbs bags, which were cloth in those days. Third, it was shipped in large cloth bags, 15-barrel capacity, that could be loaded on gondolas or flatcars. These bags had tied openings at the top and bottom. The bag was loaded through the top and opened by lifting it with a crane and opening the bottom."

Paper bags became entirely standard essentially right after WW II (and were in commercial use prior to 1940), confirming that these comments relate to an earlier era.

Tony Thompson

Most cement plants shipped both bulk and bagged cement. Cement was bagged in 94 pound bags. A barrel contained the equivalent of (four) bags. Statistically, five barrels was estimated at one ton.

Actually, the boxcars in that particular photo would have been empty, since the train was going from its home terminal of Mojave to Monolith. Most likely the boxcars indeed were for loading of bagged cement. There were no other significant boxcar customers in the Tehachapi-Monolith area then.

Covered Hoppers

Covered hoppers later became the predominant method of shipping cement. SP covered hoppers were used in moving cement become the norm as soon as SP had them, which was 1946. The change to covered hoppers no doubt was a gradual process. For example, on page 24 of the November 1974 issue of Trains there is a March 31, 1952 photo of the KI (pronounced K -"eye") local, which primarily served the cement plant at Monolith. Of the 22 cars in the train, 11 were boxcars and 9 were covered hoppers (plus two others).

The shipment of bulk cement naturally changed rather quickly to covered hoppers (there is evidence that SP did not acquire them as fast as shippers would have liked). Covered hoppers become the norm for cement service probably as soon as SP had them, which was 1946 for the conventional ones we all recognize.

Tony Thompson

Cement Plant Rail Service

There’s information presented about Pacific Readymix plants on the peninsula from the 50s into the 70s. Aggregate and cement would have been produced. The hoppers brought in aggregate for local processing. The cement produced at the facilities along Espee's Peninsula ROW were primarily for local consumption and building projects, not for shipment elsewhere. Once the cities became pretty much built-up, the need for cement declined and could generally be handled on a regional level, didn't require nearby local production.

Most of the sand and gravel would have been shipped in from Livermore and Pleasanton (originating on SP and WP, then sent up the Peninsula on the SP), with some perhaps from Los Gatos Creek (SP) and Niles (SP and/or WP?). Blending sand was shipped in from Olympia in Santa Cruz County (SP). The cement would have come from Permanente (SP), Davenport (SP), and perhaps from Redding (SP). Cement may also have been shipped in from the Sierras. Crushed stone, especially for ballast, would come from Granite Rock Co' Logan Quarry near Watsonville (SP), but gravel was preferred for concrete. Very high quality sand for locomotives, etc., would come from the Lone Star Industries' Lapis sand plant on Monterey Bay (SP).

Asphaltic concrete (or "blacktop") would also use sand and gravel. The hot plants often were next to the ready-mix plants. Tank cars of asphalt or heavy oil would be needed for blending with the aggregate.

These were the sources of aggregate for the Peninsula in the 70's, except that the Niles and Los Gatos Creek plants had closed, and Granite Rock was sending 14-car unit trains to San Jose and Redwood City.

It’s assumed in the 50s there would have been PS-2 2 bay hoppers, perhaps even into the 60s. Until late in the 1950s, they were mostly the "square-hatch" cars from GA and AC&F. Photos taken show long strings of SP cars, rarely SSW. You won’t see ANY foreign cars in these photos, though there may have been some in there.

Tony Thompson

There was a cement plant in Cupertino near Stevens Creek Road. It is the Kaiser Permanente Cement plant and SP had a local serving that plant. Brought in coal with DR&G hoppers and cement out in covered hoppers, mostly SP, and ran with a caboose till the very end. Would be quite a switching job within their yard moving MTs out of the way and loads into place.

There was a plant down near the 16th Street/Potrero(?) yard in SF that was last operated by RMC Lonestar. It was a PCA before then, it operated into the 1980s before being closed.

There was a PCA plant in Daly City along the San Bruno Branch ROW. It was eliminated in the early 1960s when the freeway was built. It had rail service, as it was too close to the branch not to have had it.

A few blocks north of the PCA plant was one operated by Balboa Building Materials, which did have rail service right up to the end of service on the branch. Gravel was brought in by rail, but the cement was trucked in. The railcars serving the BBM plant were the 2-bay ballast hoppers of varying types.

Chemical

Chemical shipping was just beginning to make use of covered hoppers in 1953.

There is photographic evidence for hoppers from anthracite carriers such as Reading showing up in California. The anthracite was apparently used in water treatment plants and elsewhere as an inexpensive “activated charcoal” for purification.

Limestone was moved along the Coast Line, both for processing of sugar beets and for use in foundries. Twin hoppers can be used for this traffic.

Copper

SP Anode Boxcars

Anode Boxcars carry bundled sheets of copper called “Cathodes”. Anodes (copper also) go on Anode flats. Anodes are 800 lb. monsters.

Copper is around the same density (considerable) in either form. You only get a little bigger bundle of sheets before you catch up to the anode weight.

Tony Thompson

The big Anodes would be much harder on the inside of a car.

Jon C.

Some anodes were shipped in boxcars. Anodes were stacked, just like the pictures show on flat cars, but on pallets.

Lee Stoermer

Modeling Copper Anodes

Go on the Plano models website and directly order copper anodes that would move on an Anode flat car. They are offering three varieties, None are exactly right for Kennecott SLC.

They offer Asarco (SP, UP) Hayden and El Paso Smelters, Freeport McMoRan (formerly Phelps Dodge) Miami, Hurley and Playas Smelters (SP, ATSF) and Anaconda styles. (GN, Milw, BN, BA&P etc) a smaller anode.

Jon C.

Cotton

SP California traffic

SP did haul much cotton grown in California. The California "Cotton Belt" is South end of Central Valley, around Bakersfield, and to some extent in the Imperial Valley. There are photos of both flat cars and PMT trucks carrying cotton bales.

Tony Thompson

On the Imperial Valley assumption, the fields mostly were direct to the west of Thermal, around the old Valerie Jean area, but up against the foothills even tighter. They trucked to Thermal, and then loaded there for shipment. It was pretty well dead by late 1950's as most loads were going direct via truck after 1955.

Eggs

Shipping Eggs on the Espee

Pictures of the Loomis depot show amongst the boxes of fruit and other freight on the loading dock are at least two crates of eggs, or so the picture was labeled. Eggs were shipped mostly by express for short regional shipments such was the case on Santa Ana Branch

When the P&SR was still under wire, eggs were shipped out of Sebastopol. In the 50's there were a lot of chicken ranches, assuming there had been many ranches in the 30's also.

It's my understanding that eggs by the dozen were shipped out of Petaluma. Early days on the P&SR would have had them going out on the evening boat to San Francisco so they could be there in the AM. On the NWP they went by rail in the overnight express boxcars so they could also make it to SF for morning delivery. There weren’t any special precautions taken to keep them cool (they were not shipped in reefers) since it was overnight service.

They went by the thousands. Remember the wooden egg crates. There were about 144 eggs per layer and most likely 6 to 8 layers per crate. "In the early 1900s Castro Valley was home to many small chicken farms of three and four acres. By 1925 the valley was ranked 2nd in the world in egg and hatchling production. It is estimated that the population of Castro Valley was 800,000 hens and 5,000 people."

These must have been shipped by rail in the 'aughts and 'teens.

Grain

Much Grain was shipped in boxcars. Often using the paper 'grain' doors. These were torn open on arrival and the load shoveled out. Some boxcars even have special small loading doors near the top for use with spouts with doors shut. The warehouse might be the location where the the blending and packaging in sacks for retail might occur. When you hear SP milling, think Aggregates.

Grain shipping in covered hoppers was off past 1953, in the future.

1895

There was a Southern Pacific Milling Company at Guadalupe in 1895. It was reportedly grinding barley at that time.

1930’s

The "newest" available Sanborn maps of Guadalupe (c.1930s?) at the San Jose Public Library website still show the large and smaller SP Milling Co. warehouses just north (RR west) of the station on the team track. These were listed as "grain warehouse".

1950’s

Mac Gaddis (conductor) told me, in my interview with him about working at San Luis Obispo in the early 1950s, that on any summer day it was not uncommon to see a cut of ten box cars of grain moving on the Coast. I would assume there could have been many more in the Central Valley.

Tony Thompson

1960-‘70s

SP had ready mix trucks and two SP milling batch plants, Goleta and Santa Barbara during the 60's & 70's. The Santa Barbara location was sold at some point to McNall bldg. mat. but received cars of Aggregates into the late 80s.

1990’s

Both buildings were later owned by the Guadalupe Warehouse Inc. and at least the larger one was still there in the early 1990s. Both buildings are visible in photos taken at Guadalupe in 1954 in Tom Dill's "Coast Line Pictorial". They are the reddish buildings in the background of the station. There was also a small B&W photo of the larger shed in the early 1990s in the Sept 1994 MR article on building a Coast Line layout.

Inside the Guadalupe Warehouse building, there they had mostly beans and seed stock from and for local growers. There was some mechanical cleaning equipment, but no grain. The warehouse burned down several years ago and Guadalupe is now building housing near or on the site.

There is not as much grain grown on the central coast of California as there has been in the past. The Mission San Antonio de Padua which is the next mission up from San Miguel was a supplier of grain and flour to many of the California missions. Also Mr. King for whom King City is named was a major wheat grower. The warehouse which was built by the RR and was staffed by John Steinbeck (the noted author's father) might have been the first "SP Milling" site.

SP in the 1990s did haul unit grain trains into the area for feeding the dairy shed. These unit grain trains produced significant revenue. In addition to the dairies, SP handled unit grain trains for poultry producers (Foster Farms, Zacky Farms) and beef cattle (Harris Ranch). UP continues to move this traffic.

Alan Davis

SP Ops & Marketing1970-1993

Lemons

From the Simi Valley though Camarillo, Oxnard, Ventura and into much of the Santa Barbara area and up into the Santa Paula valley there were many orchards of Eureka lemons. A few still exist. Sunkist was not just into Oranges but big with lemons also.

Jim Elliot

Picking Lemons

Lemons were/are hand picked and transported to the nearby [read short distance] packing houses The pickers had a metal ring and any lemon that fit the ring or would not go through was picked with clippers, no matter what the color. They would develop the color in the packing houses, sometimes with chemical treatment (Ethylene Oxide). To this day the lemons you see in stores still are all about the same size. Then they were washed, sorted, and packed in a manner to protect the lemons. In the early days they were hand packed with individual tissues.

Handling Lemons

The Southern Pacific did handle loads of lemons from Yuma, Arizona to southern California processing plants in beet gons. The fruit shipped in the gons was for processing into juice or other citrus by-products and was below grade for the fresh fruit market or an excess crop of certain grades or sizes. The wood sided cars helped to prevent damage to the lemons from the heat the was often a problem while crossing the desert.

Two lemon packing houses on the SP were at Villa Park and Tustin on the Tustin Branch. The Pacific Electric handle lemons from several locations including La Verne and Upland.

Cliff Prather

Reference

Jim Lancaster can be a wonderful source of information about the packing houses.

http://ljames1.home.netcom.com/scph.html

Lumber

The most voluminous traffic on the SP for flat cars on the Coast Line in 1953 would have been lumber for the building boom in Southern California and elsewhere in the West. Most of it came from Oregon and northern California. Because of the vital need for cars in the loading areas, SP purchased considerable numbers of flat cars to ensure that an ample supply would be available. But it must be kept in mind that finished lumber mostly traveled in box cars, particularly double-door cars (though the AAR classification for such cars is “automobile cars”), so flat cars cannot represent all lumber traffic.

Tony Thompson

A yard ships finished lumber, like a sawmill, or a receiving yard to a roof truss place, a moulding place and a plywood/ drywall place. They seem to receive about 3 to 6 cars each five days per week. Lumber shippers on the SP in Oregon (the Siskiyou Line had the most), were Weyerhaeuser, Georgia-Pacific, U. S. Plywood, Roseburg Lumber Co., Pope & Talbot, Superior Lumber Co., Medford Corp., Willamette Industries as the bigger players.

The type of lumber and time era dictated the way it was shipped -- exposed (flat car), protected (boxcar or wrapped in plastic on flat cars). Before c.1930-1945, lumber loads were shipped in about 40% box cars, 20% gons and 40% flats. After WWII the ratio shifted as car technology and the lumber industry evolved. From the 1960s onwards, you would rarely see gons carrying lumber out of the redwood belt since better box cars had replaced them.

Kevin Bunker

Lumber Loads on Special Cars

About 1912-16 there was some interest in selling pre-sized and packaged lumber and skip the local remanufacturing lumber plant. A special car was designed, built and used in the Eugene area. It had no side doors, but instead had accordian doors on the roof for top loading of packaged lumber via a crane. This was intended to set a trend and compete with the coastal vessels, but it did not.

Lumber Loads on Flat Cars

At least half the traffic was on flat cars commonly seen on SP flats heading east from Oregon and northern California. The stuff on flat cars was studs, rough lumber, etc. Each year the trade magazines had a paragraph or two on a "Boxcar Shortage" and how it would grossly affect the industry. They mention how the railroads offered flat cars, but there was a great reluctance to use them. The flatcar required a different method of securing loads, and the penny pinching sawmills wanted reimbursement for the weight of dunnage like stickers and bindings.

Appropriate loads had vertical posts and stickers between units of lumber. The over all height of the load is depended on the load. For numerous shots of different loads, try my Volume 3 on SP Freight Cars, which includes flat cars. The bracing on the top of the cars depicted may have been a bit more elaborate than was used in the 1930s, though. There are numerous photos of flatcar lumber loads in the 1910s in books (for example, p. 140 of Signor's Western Division book), with the bracing much simpler.

Tony Thompson

Lumber Loads on Gondola Cars

Gondolas were pressed into service when there weren't enough flat cars. Pages 44-45 of "Southern Pacific in Color, Vol. 2" has a photo of a freight train at Odell Lake in the Cascades probably taken in the early '50s and of the 15 cars of lumber seen in the photo, 9 were gondolas (another photo of this train, taken within seconds of this shot, is on page 168 of Church's "Cab-Foward." The going-away photo of the train is on page 175 of "Cab-Foward").

Tony Thompson

Lumber Loads in Box Cars (Auto Cars)

Most finished lumber, especially smaller sizes, usually was moved in box cars or automobile cars. Most of the sawmills preferred shipping in boxcars. They could hold more volume per weight, were not subject to vandalism and theft, and did not catch fire like on an open flatcar, and as such you ought to find more boxcars loaded with lumber than flats or gondolas in a train. The small door on the end of a box car was often used for one at a time board loading.

Molding and plywood were guaranteed to be in boxcars along with quality dimension lumber. Some dimension lumber and beams were plastic wrapped starting around the 1970's. These wraps usually had the company logo or name on them. Exposed lumber usually had the logo or name painted on the lumber bundles and also the ends of the bundles were painted.

Box cars were 50- footers to the extent that SP could lay its hands on them for lumber, and 40-foot double-doors in preference to single doors. Single door box cars with 6 or 8 foot doors were heavily used for small-stuff lumber loads that could be hand stacked: shingles, shakes, cooperage and lath. Double door boxcars (especially favored were those fitted with end doors to facilitate loading) were preferred for stick stuff, smaller posts and studs. Also after WWII the emergence of plywoods demanded double door cars since plywood was most typically loaded by forklift, also a modern c.WWII labor-saving innovation.

Lumber Loads on Bulkhead Cars

The post WW-II years saw the rise of plywood which at least until the late 1960s mostly moved inside box cars. It wasn't until manufacturers began to shrink wrap or bind plywood packets in heavy plastic that plywood started going most consistently to market aboard bulkhead or the later centerbeam bulkhead flats.

AAR guidelines for Tying Down Loads.

The AAR info for loads is on the back of the dust jacket on Hofsommer's SP history book. In a couple of those A.A.R. pamphlet that have been referred to for the years 1948 through 1953. They run up to better than 100 pages of "How to's" and Revisions and Deletions to previous issues. They tell of the acceptable wire or banding steel sizes, where to place stickers and stakes, minimum lengths of idler cars for excessively long loads, and of how to block coupler shank to lessen slack action.

In 1952 shippers were required to secure lumber loaded on flatcars by means of car stakes. One end of these vertically. Placed stakes would be tapered so as to fit snuggly into the stake pockets on the side of the car and were long enough to protrude above the top of the lumber load to allow them to be tied to a similarly placed stake on the opposite side of the car by means of a piece of scrap lumber. The number of stakes on each car depended on the size of the load, but most loads required six or eight pair. Cars thus secured were a constant headache for the railroad companies because slack action frequently caused the lumber loads to shift, and

When this happened it often broke the stakes. This then necessitated a trip to the rip track and a minimum of two or three days delay for a shifted load and even longer if the stakes were broken. On any given day one could count on finding several shifted loads on the rip tracks at Klamath Falls, Dunsmuir and other such places awaiting repair. Worse yet, the main line through Oregon and Northern California and probably other places as well, was strewn with lumber that had fallen from loaded flat cars. For most part this lumber went un-salvaged because after laying in the sun and rain for more than a day or two the boards began to curl up and became worthless. During the 1950s or 1960s, it was discovered that by tightly wrapping the lumber units with metal bands and tying the entire load together with more bands, and then allowing the entire load to slide back and forth at will on the car, most of the problem was eliminated. Now, of course center beam cars have almost completely eliminated any such problems.

Ire was also permitted for cross-tying and by the 1950s was dominant. See any photo collection for verification.

During the 1950s or 1960s, it was discovered that by tightly wrapping the lumber units with metal bands and tying the entire load together with more bands, and then allowing the entire load to slide back and forth at will on the car, most of the problem was eliminated.

No stakes were necessary and usually were not included. This was called a "floating load" on the railroad, and by the mid-1960s was the dominant loading method.

Tony Thompson

References

Pages 79-81 of the June 1992 issue of Model Railroader had an article titled "Lumber Loads From the 1940s and '50s."

See the photo on pg. 44-45 of "Southern Pacific in Color, Vol 2." The same train at the same place, taken a few seconds apart from the "Southern Pacific in Color" photo, can be found on page 168 of Church's "Cab-Foward". The going-away shot of this train is found on the top of pg. 175 of "Cab-Forward".

A photo shows a cab-forward pulling lumber loads in gondolas and flat cars is on pages 90-91 of "Southern Pacific Official Color Photography, Volume 1." The photo shows the same train as depicted in "Southern Pacific in Color, Volume 2" and "Cab-Forward," only this time the location was near Oakridge, Oregon while the other photos were taken along Odell Lake (the SP company photographer was busy that day). The other side of the train is shown in the "Southern Pacific Official Color Photography, Vol 1" photo.

Modeling Lumber Loads

Most rough lumber should travel on SP cars on your layout.

There was an article about modeling lumber loads for the 1940-50s time frame in the June 1992 MR. Also a series in RMC (January 1998?) on building flat car loads that had some AAR guidelines for tying down loads. The NMRA also have a new compilation booklet on modeling open loads. Remember to weight the cars, not the loads.

Milk Trains on the SP

Service

SP did not operate 'milk trains' anywhere in the System. But the SP did run milk cars in regularly schedule passenger trains. Most notably the valley trains to the bay area.

Tony Thompson

Southern Pacific milk train service, at least on its Coast and Valley divisions, was less of an undertaking than in other U.S. regions and railroads (particularly the northeast). By the 1940s, the service had dropped to next-to-nothing, judging from the few timetables s available. Espee's "train-of-all-trades" (and stops) on the Coast division picked up a milk service car at or near Santa Maria bound for L.A. Mark Wright Passenger Car Makeup books document a milk and cream car from Guadeloupe to LA every morning. The car might have been similar to the one in this photo (taken at Oakland, CA, ca 1946):

There’s information on a milk-express car that ran in daily Guadalupe - L.A. service during the 40s at

which indicates the car was picked up at Guadalupe by Espee's overnight Coaster (Train #70) and returned on the day mail/accommodation San Francisco Passenger (Train #71).

Paul

There were also milk pickups at Oxnard and in the Simi Valley for inbound passenger trains to LA. I don't know if any Central Valley milk wold have been hauled to LA.

Tony Thompson

No other milk trains for Los Angeles, as it received its milk from communities with large dairies, such as the San Fernando Valley to the north, Artesia to the south, and Chino to the east. All easy truck hauls, and documented in decisions by the California Railroad Commission.

David Coscia

Back in the mid 50's there were a lot of dairies south of LA in Wilmington, Carson and Torrance areas. Ben Cluff's Dairy is the name of one.

Men delivered their family dairy's milk and heavy cream in large cans twice, morning and early evening, to the Folsom Junction platform for pickup by the "Skunks" (SP McKeen motor cars) running between Placerville and Sacramento. Their milk and cream was always consigned to Crystal Creamery in Sacramento on C Street. This was roughly 1925-1935 until the last McKeen was run on the P'ville Branch and passenger service ceased. Railway Express Agency handled the goods.

Tony Thompson

The website, "Historic Centerville Depot," contains information and links to timetable samples (effective 1909) regarding local milk train service between Centerville (now Fremont), CA, and Oakland -- San Jose dairy operations.

“Milk Cars”

No private cars were used but 60' Harman baggage cars converted to milk service and lettered on the sides "Milk & Cream". See SP Historical Society Volume 3 for pictures.

It actually looks like this one.

http://www.wig-wag-trains.com/W-o-T/Wheelsotime/Harriman/153_SP.JPG

It would have been lettered Southern Pacific Lines before 1946.

“fish racks"

There was always concern among dairy farmers for keeping the milk cool. The "racks" were wooden slats above a drain pan (see for example the photo on page 230 of the book), which most sources indicate were infrequently used for fish but were used for anything that need drainage beneath it, such as any wet or iced cargo. You will find a number of the drawings of head end cars in the SPH&TS Vol. 3 which show "fish racks" usually at each end of the car. There were no fish racks in chair-baggage cars.

Tony Thompson

On the SJ Daylight one trip going east to LA made station stops like Tulare would be given milk cans to load in the Chair-baggage car, 3300 series, and then pack ice all around the cans in order to get them to LA or whatever station they were taken off at. The San Joaquin Daylight consists included a 70-BP-40-3 and 70-B-8 which had fish racks. Tulare would be 110 degree + in the summer and the baggage car would likely be hotter still. LA was a long way from Tulare. The Tulare-Hanford dairy shed has grown significantly since the 1980s.

The value of the milk would have been sufficient to make this run profitable with the added expense of the ice. That's why milk was not going from Tulare to LA on the SP. There was (is) a milk processing plant in Visalia. Most of LAs milk came from local dairies in Norco, Chino, and other east LA county locations.

This is a revealing error. The fresh milk in cans was generally NOT refrigerated in any way, except on very long runs. Any account of actual milk handling will include this point.

Tony Thompson

Nuts

The California Almond Growers Exchange (Blue Diamond brand) handled about 70% of the California crop for much of the mid to late twentieth century. Located in Sacramento next to the SP tracks it is now the world's large nut processor. From the early years of this co-op, photos of coffee sacks full of nuts show it being loaded into box cars for shipment to Sacramento. It was shipped in sacks until the late 1960s when we switched to bulk containers made from plywood. Larger growers had switched earlier. The Exchange had remote receiving locations for consolidating shipments to Sacramento. The one in our area was located next to the SP tracks but during the years of our farm it was using trucks for the relatively short haul to Sacramento. In the mid-1970s, almonds were shipped in bulk in hopper cars from Tenneco West's California Almond Orchards plant just north of Bakersfield. This probably did not involve a lot of traffic, however.

Almonds are the first tree crop to bloom (starting in February) and one of the last to be harvested (August to October or later). November shipments were driven to Sacramento because the local receiving station had been closed. In recent years the crop has become huge, but during most of the middle of last century a 100 million pound crop was large. That's only 50, 000 tons so by railroad standards not a huge volume shipper. Much of it is/was shipped overseas. The Exchange in Sacramento became so important that world almond (commodity) prices were set in Sacramento. They are California's #1 export crop. Like Sunmaid and Sunkist, Blue Diamond Almonds have been among the most successful farmer co-ops by handling the processing and marketing of the crops in addition to the production.

Note: Diamond Walnuts was a separate co-op that negotiated crop prices with processors and was not nearly as successful; processing of California crops was where the big money was made and only a few co-ops were successful in moving into that field.

Here is some info:

August 16, 1927 - Diamond Walnut plant in Lankershim was to handle 400 tons of product

Oct 1, 1934 - thieves broke the seals on a boxcar at N. Los Angeles (previous name for Northridge), 15 sacks of walnuts stolen

It’s unknown how many cars per year were shipped, but SP did have some of the business.

Nut Business

In Santa Ana Ca. the Tree Sweet loading tracks were called the Nut House tracks since the facility was once a walnut shipper. The new team track were there.

Rocks, Gravel & Sand

SP hauled sand out of Pacific Grove in the late 30's or early 40's (before Dec 7,1941), lots was hauled out in the 1950s and I believe into the 60s for various glass container manufacturing plants in the San Francisco Bay Area. Two plants that come to mind are United Can and Glass in Hayward (that served the Hunt's canneries there) and Owens-Illinois in Oakland. The sand was hauled up to the bay area, loaded on to ships, and sent to Hawaii.

A friend who grew up in Ventura who vividly remembers GP9's and RS11's on the early TOFC trains in the 1960's.

* 'Rails to Ranchos'?

** source of granite blocks for SP bridge abutments

"Rails across the Ranchos" (Loren Nicholson 1993) states that the stones for the original 1890's abutments were laid prior to track work and were hauled by wagon. No mention of the source of the stone.

Pacific Coast ran a spur (3 ft) to the rock quarry. The grade is still traceable off Foothill Blvd. The Presbyterian church and the Carnegie library bldg. (now SLOC Hist Soc) are built of that stone, which is volcano core basalt, dark gray in color. SP abutments and culverts are of a different stone, brown-tan. There are vague references* to that spur originally (pre WW1) servicing a (granite) quarry* (now separated from the "tracks" by Hwy. 1) at the base of Cerro Romaldo.

There was not a whole lot of on line business on this section of track above Sinton. There was a grain elevator at Saint Paul the local industries in Beeville, Pan American Gas had a siding in Burnell. There was also several elevators an industries in Kennedy that used the railroad. The real reason for abandoning it was really started by SP when they could no longer afford the upkeep on it.

Seafood Shipments in Reefers

Fish was a major source of express revenue until the advent of reliable and reasonably priced air cargo services. I'll bet you could order fresh Atlantic cod in Chicago restaurants by the1920's at least. Somewhere there were cars equipped with special tanks for live fish -- and not the fishery cars either.

There were fresh fish shipments in express reefers and frozen fish shipments in heavily insulated cars which includes the 1930's-40's time frame I am sure this was not restricted to PFE. Read the PFE book.

Tony Thompson

The book on the Espee commissary system mentions salmon being shipped from a fish wheel on the Columbia River all over the system under ice for company use in dining cars and fixed dining facilities. Locations as far away as New Orleans were mentioned. Express Reefers carried loads of fresh shrimp and oysters from New Orleans to Laredo via San Antonio. Express Reefers were American Railway Express (Later REA) carried from New Orleans to San Antonio by the Sunset Limited.

Almost every baggage car had fish racks and floor drains for various commodities to be shipped under ice.

Fish Meal Railroad Operations In L.A. Harbor

On transporting fish meal, Andrew Zankich had some input on practices in L.A. Harbor. For a time he worked for Star Kist Foods on Terminal Island in Los Angeles Harbor during the 1960s. He said that fish meal was processed in the Reduction Plant and was shipped in fifty pound bags by truck and boxcar. Rail sidings for Star Kist were in the middle of wide streets. Boxcars were loaded with canned tuna and pet food in addition to fish meal. Tank cars brought in oil for the canned tuna pack. The "Spring Water Pack" was still a number of years off at that point.

Continental Can had a plant on the island and these cans were brought over by truck. (It's possible that Continental got their can stock by rail but that would need to be checked.) The cardboard boxes were brought in by rail.

The Harbor Belt Line serviced the L.A. Harbor until 1998. Depending on location, the SP, Santa Fe or UP could handle traffic. Star Kist was served by SP.

Steel

Except for the Kaiser plant in Southern California, all other west coast steel facilities primarily processed raw iron and steel into useful forms. Other plants with melting and casting facilities were NOT steel-making plants, they just reprocessed steel made elsewhere.

Tony Thompson

Kaiser Plant

The only integrated steel mill on the west coast of any consequence was the Kaiser plant in Fontana (west of San Bernardino). It made steel from iron ore and other raw materials. That can still be a pretty enormous industry, rolling mills alone are really huge buildings. The Kaiser steel plant was served by both SP and Santa Fe. The plant had no water access so raw materials were delivered by rail.

Tony Thompson

It was opened in the 1940's. Espee used to hold the ore cars on south side of I-10. Then in one painfully slow train pull them Northerly in underneath the freeway on present track, crossing Valley Blvd., then to the north side of lot where the blast furnaces were. The Chinese came along in late 1980's bought the cupolas and sent them via boat to Shanghai. They were too dirty to operate anymore inside the U.S.A. The water tank is about the only remnant of the blast furnace area. Out in this northern area is also where the Santa Fe had a yard set at an angle. BNSF has the large B yard just east of Cherry avenue now. The finished steel seemed to be mainly hauled north out via Santa Fe, but the Espee hauled in the raw ore from the south.

Oregon Steel Mills leased out the area from Kaiser Resources, then sub-leased it to California Steel Industries beginning in the late 1980's. Today, this is where the switcher works with cars.

On the south side of the freeway, just to the east of Etiwanda is where Liquid Air used to be. They manufactured much of the gases used for torch work inside the mill. Once the mill went cold, Liquid Air sued the company for lack of business. They expected the Fontana plant to be perpetually open.

Paul Vernon

Modeling the Kaiser Plant

If you want the whole enchilada from delivery of iron ore and coke and limestone, to iron-making in blast furnaces, to making steel in open hearths or basic oxygen furnaces, you'll have to model Kaiser.

Tony Thompson

Judson-Murphy-Pacific

In the East Bay there was Judson-Murphy-Pacific in Emeryville near the US 80-580-880 merge as you approach the Bay Bridge. They had and large steel/galvanized metal buildings. You would see gondola & flat car loads out for structural steel and a large area set aside for scrap metal.

Vince Vargas

USS POSCO

The USS POSCO in Pittsburg, California is a steel mill that has been around since the early 1900's when it had a 150 ton hearth. The first Pittsburg steel facility opened in 1910 as a 60-man foundry under the name Columbia Steel. Consisting of one building and a single 150-ton open hearth, the plant furnished steel castings for the dredging, lumber and shipping industries.

In the 1920s, the plant expanded to include the West’s first nail mill, and later, the first hot dip tin mill west of the Mississippi. During the 1930s and 1940s, facilities and equipment were added to help supply major public works projects – the most notable being the San Francisco/Oakland Bay Bridge – and to meet the demand for steel products during World War II.

Over the next two decades, the plant’s single-sheet feed operations were replaced by more efficient cold rolling mills and continuous feed lines. When a pipe mill was added, the Pittsburg facility gained the distinction of having the most diverse product line of any steel plant in the United States.

Steel Traffic

On the Coast line in 1949 from Guadalupe to King City, the traffic that would move up or down the coast, to or from steel plants would be scrap metal, no iron ore and coal (they can come from anywhere). Most western steel was oriented to rolling mill products (sheet, structural shapes)

Tony Thompson

Most of that traffic would move out over the Overland Route and not up and down the coast. You could receive some finished products such as steel shapes and (if they made it) wire, always good loads in gons. Used in things for bridges and larger structures etc. Another possibility is the routing of things like Limestone and Dolomite which may be handled up the coast to the plant.

Jon C.

Coke came from Callendar. Coke production there didn't start until 1955 or thereabouts. They would move in GS gons.

Tony Thompson

Sugar Beet

Mill Traffic

From 1890 to 1950 or so, you will have a lot of diverse rail traffic to and from your sugar mills. Most SP fans are naturally familiar with the infamous "beet racks" and the annual beet campaigns of legend.

Prior to the arrival of the Class G-50-20 composite GS gondolas in 1948, SP moved its sugar beet traffic in Blackburn patent beet racks temporarily attached to flat cars. Once the G-50-20 cars were on the property, they dominated the sugar beet rush, but some steel GS gondolas were also pressed into service.

The beet trains were considered perishable and expedited handling was required.

Wesley Fox

Beet Refineries

The map on pages 26 and 27 of SP Trainline no. 69 identifies 10 California sugar beet refineries as of 1960 served by the SP. Two are north of Oakland: Hamilton City (Holly) north of Colusa and Sugarfield (Spreckels) north of Davis. And the Holly Plant at Tracy would be near due East of Oakland. There was a big Spreckles sugar beet refinery in Manteca, right beside HI99 & the 120 crossover. Beet gons frequented the site.

Holly Sugar in Hamilton City received beets from both the south and north (Tule Lake south of Klamath Falls). In the late 60's you would see besides gondola loads of beets in and lots of boxcars also covered hoppers and tank cars. The tank cars carried fuel to run the plant.

In 1980, bottlers and canners changed over to high fructose corn syrup. That change in sweeters would, along with other conditions, start the steep decline in growing of sugar beets in California.

Inbound traffic

Sugar beets, coke and limerock are brought in by rail. The train that would bring the empty beet gons from the Holly sugar factory at Dyer (Santa Ana Ca) would usually have a couple of UP gondola in limestone service and one or more tank cars ahead of the beet racks.

Beet Pulp

Beet pulp, the by product of the slicing of the beets, is dried and shipped in pellet form either in bags in boxcars or in gravity flow covered hoppers.

Back in the 50's and 60's in Utah the local Utah-Idaho Sugar plant shipped sugar, molasses and beet pulp.

Beet toppings and the dirt off of the beets were sent to the cattle feed lot, operated by the sugar mill. Beet pulp was dried and sold in bulk some was trucked and some by covered hopper. Beet pulp was bagged in 50 lb paper bags in the late 50's.

Limestone

From photos of the limestone bunkers at the smelter at Selby, the limestone was transported in drop-bottom gons (the ever popular GS Gon). The lime rock was cooked in a coke oven and slacked (crushed) into powdered lime for filtration. Limestone in gons was very common, Kaiser steel's limestone came in gons off the Santa Fe's Lucerne Valley Dist.

Coke

Lots of beet sugar plants were coal fired, so that came in from the Powder River Basin or other mine locations. The burning of the coke provided the heat to slack the lime and produced pure co 2 for use in the plant. In the early days of the plant in Woodland fuel oil for the boilers was supplied in tank cars, plant later switched to natural gas.

Natural Gas

California beet plants in the 60s onward were natural gas powered. Those tank cars were for liquid sugar for the canneries and bottlers. Fuel must have come in 10,000 gal tank cars or was it piped from some place.

The old Great Western Sugar plants used Powder River Coal, probably Holly did too in the MT and WY. California plants for sure, were natural gas fired, at least from the sixties to the end. The Powder River Basin was a source of coal for the mills on the Great Western in Colorado, but not so much if at all on the SP. Coal sources were much closer to the mills in the early days. Remember also that the Powder River Basin didn't really get going as the huge coal fields that are there today until the late 1970s. This is long after the California beet sugar mills had converted to natural gas as their primary heat source.

Outbound

Molasses

Molasses (essentially a mid-step in the sugar refining process). Molasses comes after the sugar is extracted from its source, either beets or cane. Probably there was moving more by truck than by rail by the 1960s... remember, this stuff has to stay heated to flow.

Molasses goes in tank cars, usually in leased cars. Depending on where the source is, it is either trucked in or come in gondolas and a clam shell shovel unloads it. Remember the SP tank cars with the black "S" in a white diamond on the dome, for sugar loading.

Corn Syrup

You will see corn syrup tank cars at Crockett and other sugar plants in the modern era. This enriches the process and hastens sugar extraction.

Tony Thompson

References

Don Strack has compiled several pages of info on Utah’s sugar beet history at utahrails.net/industries/ sugar.php.

Another link focuses on Southern Pacific’s operations.

www.pwrr.org/prototype/sugarbeet/ index.html

As does an old Trainorders thread at: www. trainorders.com/discussion/read. php?1,75428.

Sugar

Circa 1950

Sugar was not shipped in bulk by SP. In 1950, sugar was still going out of Crockett in sacks in box cars (in addition to the supermarket retail cardboard boxes, also shipped in box cars). The same was true at other sugar plants along SP rails, including Spreckels, Holly and others.

A few years later, they converted some box cars to hopper service, with nearly vertical slope sheets inside, as was needed for sugar to be unloaded by gravity alone.

Circa 1960

A decade later, the sugar then goes to drying pans and then either loaded into the airslide or gravity hoppers or sent directly to the sugar bins (silios). The General American innovation, "Airslide" technology, took over this traffic category.

Tony Thompson

Sugar is loaded in airslide covered hoppers (preferred by most industrial customers) or in gravity-flow covered hoppers. It is also bagged in 25, 50 or 100 bags for industrial use and loaded in plain boxcars ( floor loaded) or on pallets in cars with D/F equipments. Little 5 and 10 lb. bags for grocery stores are in small wrapped bales of 16, palletize and sometimes loaded in D/F boxcars. A small portion goes intermodal, but mostly on interstate trucks. It was also shipped in bulk in 2000 lb. tote bags in 60 ft boxcars to other food processors, all sizes of retail bagged sugar was shipped in boxcars.

Sugar is moisture sensitive. You don't want to load sugar right off the drying pans into a rail car, unless you are going a short distance like factory to factory. It will set up like concrete. Still, even being careful, some cars do arrive hard at the customer's dock, especially if the car was loaded with just cooled sugar. Bags get hard too, especially if storage in a humid location.

Outward shipments would include covered hoppers and boxcars of bagged, packaged sugar, no doubt on pallets and wrapped in plastic or paper.

Reference

The 1994 Pentrex video titled "Imperial Valley Sugar Beet Trains" shows the process from harvesting to the packaged product, and also shows the loading and unloading of the GS gons and steel hoppers.

David Rowe http://www.pentrex.com/vr074.html

On page 9 of SP Trainline no. 69, within the article "Sugar Beets and the Southern Pacific," lists SP-served beet sugar mill of Holly Sugar at Carlton (Brawley).

Vegetables Shipping

Hollister California

San Benito Foods yesterday. They are a tomato packing plant. The facility runs about 65 to 80 days per year, coinciding with the tomato harvest. Packing starts around July 4 and runs into early/mid September. Catch the action then. (Train, not tomato packing).

San Leandro, California

San Leandro was really big for cherries and peaches. The "current" San Leandro depot (now the home of the San Leandro Historical Railway Society) was built in response to complaints by farmers in the area that the early depot was not large enough to handle their produce shipments.

Wheat

Early Movements

When S.P. first began to handle California wheat in bulk (as opposed to in sacks or bags, in box cars) about 1920 did it have dedicated gondolas or hoppers assigned for that purpose and what distinguished them from other equipment?

Bulk wheat at was transported in boxcars. The door openings were partly blocked off with cardboard, plywood or plain boards (and later on the Signode Grain Doors), then the wheat was loaded. Unloading involved removing the boards, letting as much as possible of the load flow out, then manually shoveling and sweeping the remainder.

In Canada boxcars were used (on a limited scale) for transporting wheat up to the late '70s.

Often, outside sheathed boxcars were sheathed part way up on the inside to allow loading of bulk commodities (without that lining, the grain, coal, or whatever would push against the outside sheathing, tending to loosen the boards from the frame). Also, boxcars were marked on the inside with load height limits for various commodities. Lettering sets don't include those inside markings.

While the boxcars had a line for loading, the elevators did not pay an attention to them. They did not sell wheat by the pound/ton. It was sold by the bushel. So the the operator knew what his wheat weighed by the bushel and he loaded so many bushels. He could tell you what his load weighed because he measured it in the elevator before it ever entered the car.

Wine

SP hauled enormous amounts of it, though not in their own cars.

Tony Thompson

In the early years tank cars were used. Loads moved in wine tank cars and insulated boxcar loads (barrels inside) from SP subsidiaries Northwestern Pacific (accessing both Sonoma and Napa region wineries and port distilleries) and the Central California Traction Company out of its Sacramento, Lodi and Stockton interchanges (specialized wine tank cars carrying bulk wine, mostly). So, too, did the Western Pacific and Santa Fe get wine loads from their CCT Stockton interchanges. Note that the CCT was tri-owned by the AT&SF, SP and WP.

Not much wine traffic, however, moved during Prohibition...with the exception of sacramental wine (mostly port) which was exempt from the Federal dry laws during those years.

In the 50s and 60s ex-milk cars were used.

You can see some of these at this web page: http://tinyurl.com/yomnqe

A blog on the discussion of wine shipping and a little about wine tank cars (good models and bad). The intent was to clarify the wine business for anyone wanting to model this industry, or to handle wine tank cars on their layout. Here's a link:

http://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2012/02/wine-as-industrial-commodity.html

http://modelingthesp.blogspot.com/2012/02/wine-as-industrial-commodity-update.html

Tony Thompson

Photo courtesy of Brian Moore